This post was originally published on Medium

The Business Model Canvas is a great tool at any stage of a business’s growth. I started using it in 2010 when the companion book was published. I have done so with individuals, startups, scale-ups, and turnarounds. You can use the canvas to document your strategy, or to pitch investors and prospective partners. But where it excels is as a scaffold for creativity, since it forces you to address the fundamental building blocks of any business design.

Nevertheless, I have found a few areas in the canvas where people get lost or confused when they try and use it for their own business. Sometimes it’s because they try and fill the blocks out in the wrong order. More often than not, they do not really know how to go about answering the questions relevant to each block. They may understand the concepts, but not how to translate them into practice.

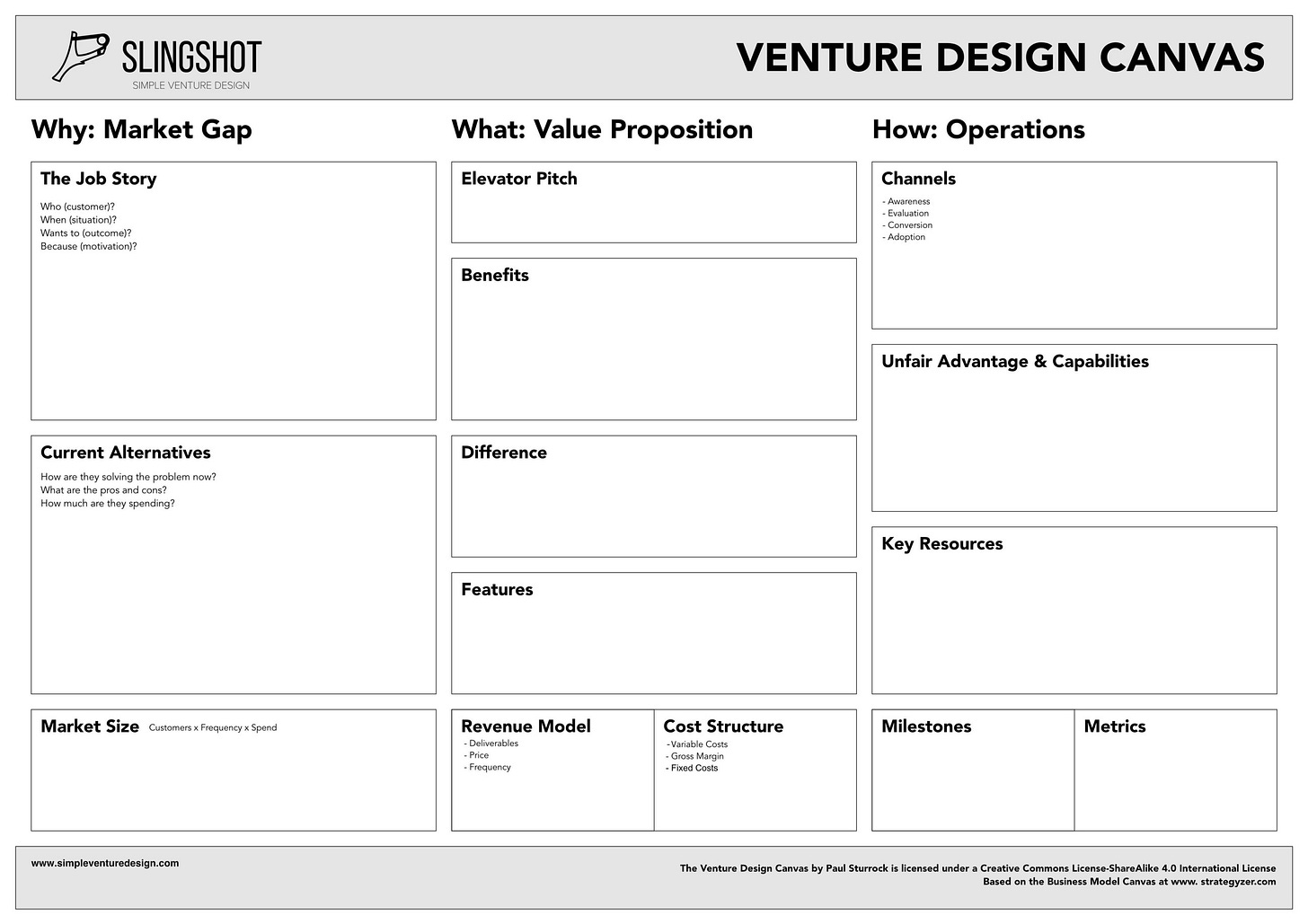

Earlier this year, I decided to design a new version of the canvas. This version is informed by the original Osterwalder/Pigneur canvas as well as Ash Maurya’s Lean Canvas. But it is primarily based on my experience of what does and does not work, after practice with a wide variety of teams. My goal was to design an accessible and practical tool. Working with a new cohort at FFWDLondon gave me an ideal chance to test out my ideas. After a few further iterations, it is now in shape to share with a wider audience.

The Venture Design Canvas is an evolving document, so I am eager to hear your ideas about how it can be improved. The main changes compared with others’ versions are summarised below.

The sequence

I have tried to clarify the ideal sequence of steps for designing a business model.

People tend to approach the business design process from a range of different perspectives. If they are already in business, they already have a business model — whether they know it or not. Their model may not be working well and they are trying to figure out what needs to be changed. Or it may be working brilliantly, but they know that they need to do something different to get them to the next stage.

In all cases, it is best to go back to first principles and document their current model. It is a great way to reveal that what people think is the problem often is not the real problem. That often encourages them to ask themselves how they would design their business if they were starting over.

In the case of startups, or would-be entrepreneurs, you tend to find they start from one of three points:

1. Their capabilities. Which is fancy jargon for their skills, or some other resource, such as property, which can be turned into an “unfair advantage.”

2. Their idea for a product or service.

3. A gap in the market. That is, a group of customers with a problem or hunger that is not being adequately addressed.

You can think of these as the answer to three different fundamental questions about a business and its product or services. Capabilities answer the question “How are you going to do this?” The idea answers the question “What is your business?” Only the gap approach answers the question of “Why should your business exist?” You have not got a viable business idea until you have answered that third question. Building the wrong thing right is a classic way to fail.

I am a big fan of Simon Sinek’s dictum to always “start with why”. So I redesigned the canvas around a structure that forces the conversation back to square one, by asking the questions below in the right order:

1. Why should your business exist?

2. What is your promise to the customer?

3. How are you going to deliver on your promise?

Why should your business exist?

The Why section is about identifying a gap in the market. The best way to do that is by finding a minimum viable segment.

The original Business Model Canvas also has a section for the customer segment. But the problem I have encountered in practice is that it is not granular enough. People understand what a customer segment is at an abstract level, but they often struggle to translate the concept into something they can work with.

There seem to be two reasons for this struggle. The first is that picking a segment is a difficult decision. People have a big vision for their product or service. Picking a customer segment requires you to recognise that the only way you are going to get to that vision is by making a concrete and limited choice today.

The second reason is that they struggle with how to define a segment and fall into the trap of doing it in a way that fails to meet the test of a real segment. That is, a set of people with the same need, the same criteria for selecting competing products, who get their information about the category of products through the same channels. For me, the best approach for cutting through this confusion is Clayton Christensen’s “Jobs to be Done”. So I have made his questions explicit in the canvas to focus and provide some essential discipline to the difficult task of sifting through alternatives for segmentation.

Making a difference

The other big gap I have found in the original Business Model Canvas is the issue of competition and differentiation. Osterwalder has explained why he excluded it, believing that it is external to the business model. I understand this argument in theory but it does not work for me in practice.

To attract customers, you need to be different from the status quo, which means you need to thoroughly understand the status quo. So the Venture Design Canvas explicitly asks you to explore what your customer’s alternatives are.

What is your value?

Only once you have established why your product is needed, by defining a “job to be done”, can you begin to design a value proposition that addresses that gap.

Again, my problem with the Business Model Canvas is the need for more concrete granularity. Osterwalder, Pigneur and colleagues have now released a Value Proposition Canvas to address this. I guess it is a matter of taste, but while his “vitamins and pain killer” metaphor is useful, I prefer a more traditional approach. The test of a good value proposition is whether it convinces the customer that it can improve on current practice.

I have tried to ensure that the value proposition meets this test and avoids common pitfalls that I have witnessed in the past. The first step is to lead with benefits. Customers only buy because the experience will leave them better off. If you cannot articulate that clearly, you do not have a value proposition.

Benefits are sometimes difficult to articulate in isolation. They can seem overly abstract and conceptual. Comparing yourself to the next best alternative will help you to be both concrete and persuasive. The features that deliver the benefits and the difference are the last — but least important — element of a value proposition. It is essential to list these separately. Otherwise it is too easy to confuse them for benefits. A “So what?” reaction indicates that it is a feature not a benefit.

The Revenue Model

Your revenue model is another excellent opportunity to be creative and differentiate yourself. Sometimes merely making something digestible makes it a better deal. That is why we like subscription deals and other revenue models that split payments into small chunks. It’s also an opportunity to lower the customer’s risk of buying an unknown product. I don’t want to go into detail here as it would make this post to long. But I have added a section to the model which specifically asks you to define your revenue model.

How are you going to make it happen?

Once you have determined what you are offering and why, you are ready to move on to the last section, which is about how you are going to deliver it.

I’ve made some tweaks in the model in this section. The most important one is integrating the concepts of capabilities, unfair advantages and key activities into one section. Again, I won’t elaborate about that today as it merits a post of its own.

Does this help?

Those are the main changes I have made in the canvas. You can download a copy here.

For me, the test is whether it is a more useful tool for business model design in practice. I have tried to do that by providing a clearer structure.

Thanks for reading this far. If you liked it, please encourage me by liking it below. If you’re a subscriber, you can also let me know what you'd like to see more or less of. Or tell me about tools, programmes, etc. you'd like me to feature.

If you know anyone who might find this useful, please forward it to them.